If you’re lounging as you read this, the next sentence may scare you sit-less: “Sitting is the new smoking; it’s just as insidious,” warns Marc Hamilton, Ph.D., a professor of biology and biochemistry at the University of Houston.

Hamilton is making a point about how so many Americans are letting their leg muscles — and therefore their bodies — turn to mush. “You’ve seen the flat line on an EKG when all the doctors rush in? That’s what’s happening to your leg muscles when you’re sitting,” he adds. As he speaks, I flashback to a job I had at a digital agency: I showed up on my first day of work in the New York City office to find half the staff standing at their computers. Because they didn’t have chairs. The office consisted mostly of makeshift desks about waist-high that we would belly up to bar height. (More: 3 Crucial Exercises to Combat Desk-Job Body)

Turns out my hipster coworkers were onto something. “Standing while talking on the phone or filing isn’t exercise by anybody’s standard, yet compared with sitting, it increases your metabolic rate a bit,” says Hamilton. In case you were wondering, doing “light office work” while sitting burns 96 calories an hour for an average 140-pound woman as opposed to 147 calories while standing, according to a widely accepted compendium of physical activity. But more importantly, “when we’re sitting for extended periods, hundreds of ‘bad’ genes are turned on, including ones that stimulate muscle atrophy,” adds Hamilton. (See also: 5 Ways to Build Bigger, Stronger Glutes That Have Nothing to Do with Squats)

Intrigued, I head to the Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center to see firsthand the toll that opting for a chair and a laptop all day is taking on my leg muscles. Once there, Barry R. Chi, M.D., chief of physical medicine and rehabilitation, wires my leg muscles with surface electrodes that are tethered by several long cables to an electromyography (EMG) machine. I reenact a day in the life of my legs by sitting, standing, walking (in both heels and flats), rising up on tiptoe, and jogging. We cap this off with squats and lunges as a yardstick to measure everyday muscle activity against.

True to the EKG analogy, the leg muscle readings on the EMG monitor are indeed flat lines when I sit in a chair — it's as if I'm not even there. But something happens when I stand up in front of the monitor: It fills with electrical activity. "You may not feel anything, but your leg muscles are now supporting your whole body weight, and all of your big muscles of the body are now engaged in isometric contractions," says Dr. Chi, pointing to the elevated lines. "Standing for two hours can be the equivalent of going for a two-mile run," he explains.

Interestingly, when I stand or walk in heels, my quads and hamstrings show greater surges than when I’m in flats, but Dr. Chi quickly warns against long-term side effects of wearing heels, such as back pain.

How Genetics Alter Your Leg Muscles

The length of your legs is basically a matter of genetics — and this could mean way, way back in the family tree. In general, women are slightly leggier than men: The latest body-measurement statistics from a SizeUSA study, conducted by TC², a not-for-profit apparel industry resource, show that the average 18- to 45-year-old woman’s legs (determined by crotch height) make up about 45 percent of her total height versus 44 percent for the average man in the same age group. (More: Is It Actually Harder to Lose Weight When You’re Short?)

Leg muscles are another story. They depend greatly on your genes and what you do with them. The latter half of that equation will be discussed later — i.e. diet, exercise, couch-sitting habits — but for now, a quick leg muscle anatomy lesson.

Everyone has the same main leg muscles: quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, shins, and calves. Within those larger muscle groups, though, there are several smaller muscles, each with their own unique function(s) — adduction, flexion, extension, rotation. For example, the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris are all part of the hamstrings. It’s worth noting that while adductor muscles are located on the inner thigh and help to move your leg into the mid-line of your body, abductors are not merely “outer thigh” muscles, but rather muscles located in the glutes that help rotate your hip. This story will be sticking to the muscles below the booty. (But here’s a guide to your butt muscles if you’re interested.)

But there’s a wide range of sizes and muscle makeup among people that even experts debate. “Muscle fibers in humans evolved so that most of us have leg anatomy with a majority of slow-twitch fibers, which give us our staying power during long runs,” according to Daniel Lieberman, Ph.D., professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University. “We’re built more for endurance, whereas chimps have more fast-twitch fibers,” he explains. With fewer powerhouse fast-twitch fibers, humans are at a disadvantage when it comes to speed. “As a species, we’re terrible sprinters,” says Lieberman. “Cheetahs can run 25 meters per second. The fastest human, [Jamaican world champion sprinter] Usain Bolt, runs only 10.4 meters per second,” he adds. (See also: Everything to Know About Slow- and Fast-Twitch Muscle Fibers)

It turns out that the quadriceps, or quads, are the real wild cards of your leg muscles, as they can range from predominantly fast-twitch to the complete opposite: The quads of someone like Bolt can contain up to 90 percent fast-twitch fibers, says John P. McCarthy, Ph.D., former professor of physical therapy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. On the other hand, elite marathoners’ muscles can contain up to 90 percent slow-twitch fibers. The quads of average people, or even those of swimsuit models or hulking bodybuilders, are more a fifty-fifty mix of the two.

The problem is that many people are often so afraid of getting bulky thighs and calves that they neglect to strength-train their legs. But actually, bulky legs are mainly due to fat. “Our legs can go from shank steak to marbled rump roast without our even knowing it,” says Vonda Wright, M.D., a double board-certified orthopedic surgeon based in Orlando, Florida. “It’s a snowball effect when we start accumulating fat, and it affects the function and strength of muscle,” she continues. (See: Fire Up Your Lower Body with This Beginner-Friendly Workout)

Body Composition of Your Leg Muscles

If you were assigned female at birth, your hormones have been signaling fat cells to be stored around your butt and thighs since puberty, ultimately to help serve as reserve energy for pregnancy and breastfeeding. “Women tend to gain fat in very specific body parts, mostly those from the waist to the knee,” explains Andrew Da Lio, M.D., professor and chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles. The most common of those parts is the outer thigh, he says.

There are two levels of fat in the legs: a superficial layer and a deeper layer, explains Dr. Da Lio. The superficial layer is where you’d find cellulite when fat pushes through between the tissues that connect the skin to the underlying muscle. Gain too much of the deeper leg fat and it can actually begin to infiltrate your leg muscles, says Dr. Wright. The good news? This deeper layer is also typically the first layer of fat to shrink when you exercise. (For more: Try This No-Equipment Leg Workout When You Can’t Make It to the Gym)

How to Strengthen Your Leg Muscles

Last fall, with the help of the UCLA Center for Human Nutrition’s Risk Factor Obesity Program lab, I tried an experiment. I did every exercise I routinely avoid on the chance it would make my legs look like Schwarzenegger’s: dozens and dozens of squats and lunges each week combined with the stair climber and cycling classes. And a funny thing happened: I lost 10 percent of the fat from each thigh in four weeks, according to the lab’s DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) body scanner. By eight weeks, during which I also stuck to a low-calorie diet, I’d lost more than an inch from each thigh.

“You can change the composition of your leg muscles — the ratio of fat to lean mass. Increasing your strength and endurance will lead to a change in how your legs look,” says Dr. Wright. And there was my proof in the form of the X-ray-like DEXA readouts, which showed that the grayish halo representing the fat on my thighs was shrinking.

But here's the kicker: The darker center consisting of my quads and hamstrings wasn't busting at the seams after those gazillion squats. In fact, it had pretty much stayed put, which is the moral of this story. If I hadn't done those reps while I was dieting, my muscles probably would have shrunk a little, too, and along with them, my metabolism.

Stronger legs may indeed be a secret to maintaining a healthy body. “When you increase the strength and endurance of your legs, it generally makes it easier to exercise and move around, leading to greater physical activity throughout the day. You burn more calories overall,” says McCarthy. In fact, a University of Alabama at Birmingham study found that women who maintained weight loss one year after dieting had much greater leg strength than those who didn’t. (Also: The Best Leg Day Exercises Trainers Want You to Add to Your Workouts)

But What About Your Ankles?

The region between your calves and ankles is not defined by muscle but rather by the Achilles tendon, which connects the two. For some, this area cinches in dramatically from a well-toned calf muscle, while for others it slopes down gradually. And then there are those whose lower legs appear to drop in a straight line with no indentation at all, inspiring the unflattering and totally body-shaming label: cankles.

“Cankles are essentially a visual effect,” says Dr. Wright. “Models often look as if they have cankles because their legs are tubes from the knee to the ankle. It’s all relative,” she says. (More importantly, here’s how weak ankles and ankle mobility affect the rest of your body.)

For the calf to have the appearance of tapering, there has to be a bit of muscle size to the calves. Yet, again, many are reluctant to strengthen their calf muscles for fear that they will thicken and produce a cankle effect. "That's a myth. Cankles don't come from muscle, because by the time you get to the ankle, it's all tendons," explains Dr. Wright. It's a matter of genetic roulette, fat accumulation, and body composition.

Okay, now that you've gotten a lesson on how and why leg muscles look and act as they do, here's a breakdown of exactly what your leg muscles are and where you find them.

The Anatomy of the Leg Muscles

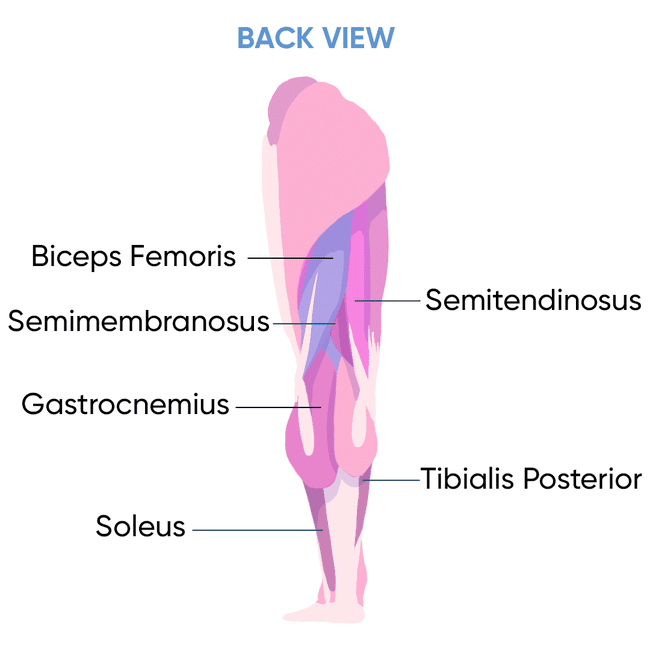

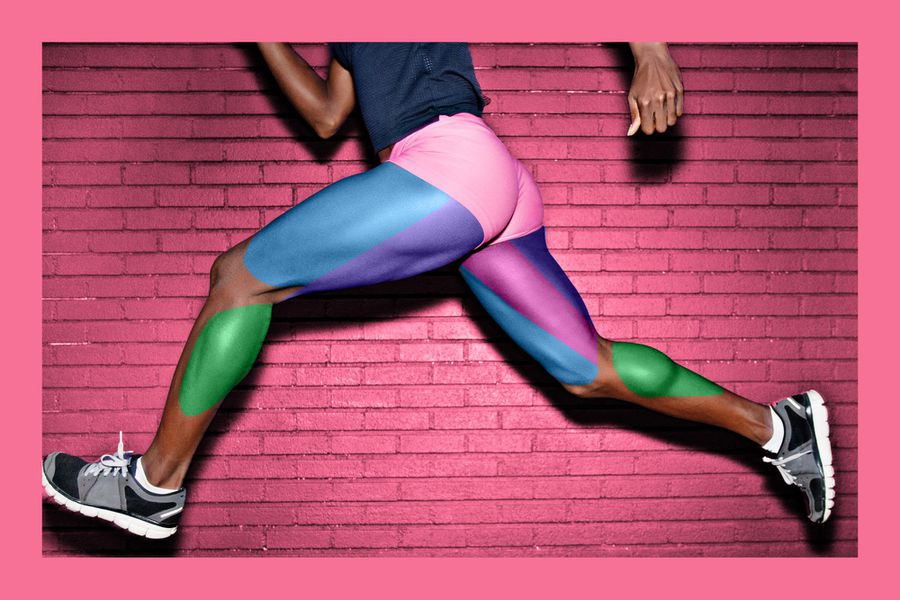

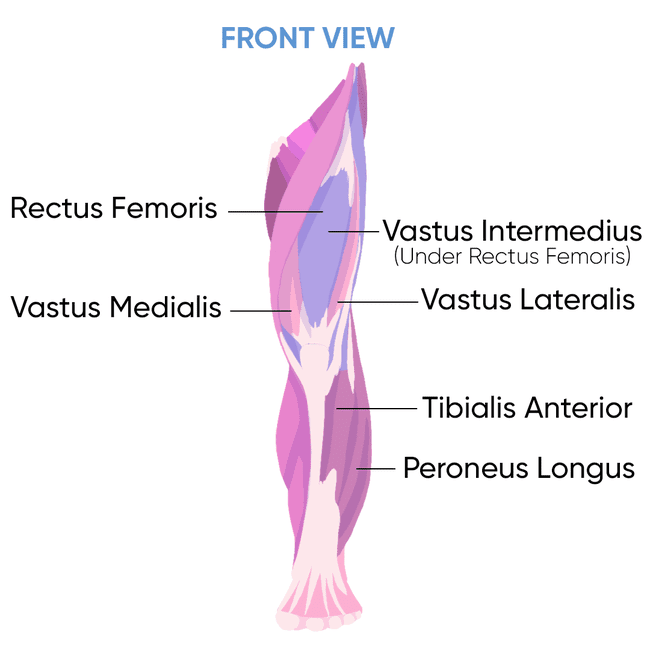

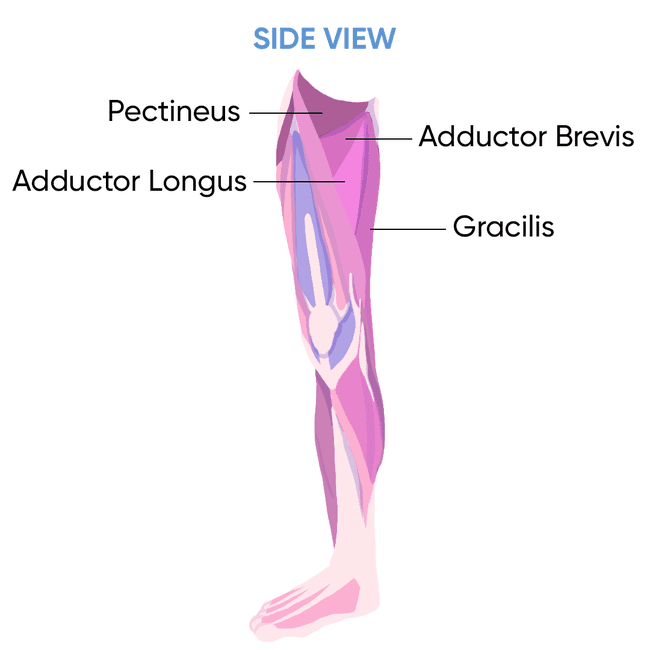

Take a look at the labeled leg muscle diagrams below for a more detailed look at the front, side, and back of your leg muscles.

Front Leg Muscles

When it comes to the front of your legs, there are two muscle groups — the anterior upper leg muscles (i.e. your thigh) and the anterior lower leg muscles (i.e. your shin). There are four parts of your quadriceps: rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius. The tibialis anterior is the strip of muscle that makes up your shin and helps you flex your ankle to move your foot toward your knee.The peroneus longus runs down the outside of your anterior lower leg.

Side Leg Muscles

Your inner leg muscles or inner thigh muscles are known as your adductor muscles, which include the pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, and gracilis. This group of leg muscles is responsible for bringing your thigh toward the center of your body, as well as rotating the thigh bone.

Back Leg Muscles

The posterior leg muscles (below the glutes, at least) are what make up your hamstrings and calves. The three hamstring muscles — biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus —are responsible for flexing your knee and extending your hip. The calf muscles include the gastrocnemius, the uppermost of your two that gives your feet power with each step, and the soleus, which lies underneath the gastrocnemius. The tibialis posterior is a very small muscle deep inside the calf that helps stabilize your foot.